Seal vs. Sea Lion: Your Guide to Knowing the Difference

- Enrichment

- Behavior

- Natural history

As the world’s largest marine mammal hospital, The Marine Mammal Center cares for an extraordinary number of animals—not just in the number of patients, but also in the variety of species and medical conditions. Seals and sea lions of multiple species are our most rescued animals. They may be orphaned, diseased, injured or entangled in ocean trash.

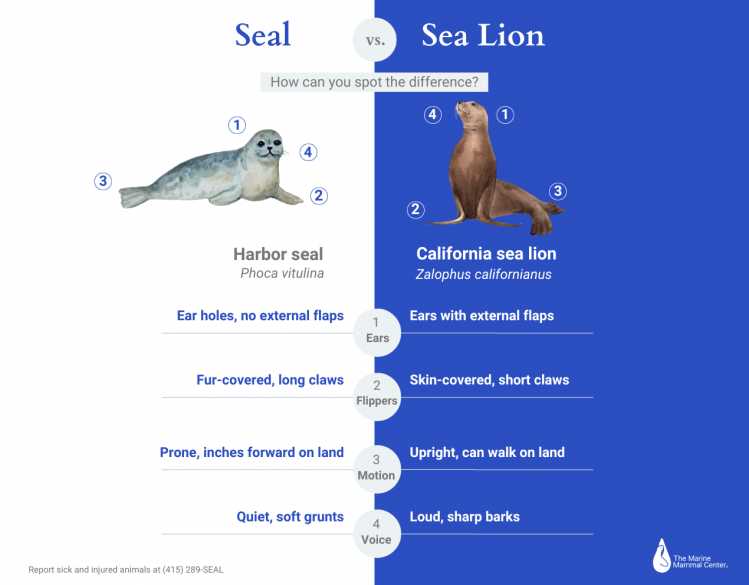

Seals and sea lions are both pinnipeds, which means they have front and rear flippers. While these sleek, flipper-footed marine mammals may look similar at first glance, they are distinct families of animals with unique characteristics. From how they look and behave in the wild to how we care for patients at our hospital, learn how you can tell the difference between seals and sea lions. Let’s dive in …

Physical Differences

Do seals have ears? One of the most obvious ways to distinguish seals from sea lions is by looking at the sides of their head.

Sometimes referred to as true seals or “earless” seals, marine mammals in the phocid family, such as harbor seals, have ears and hear very well, but do not have external ear flaps. Instead, true seals can be identified by their small ear holes.

Unlike true seals, sea lions and fur seals have external ear flaps; these animals are in the otariid family and are sometimes called “eared” seals. (Fun fact: Despite having the word “seal” in their name, fur seals are more closely related to sea lions than true seals!)

While all species of seals and sea lions have adapted pristine agility in the water, it’s easy to spot another difference by observing their flippers and how they move around.

True seals have smaller front flippers and swim by moving their rear flippers side to side like a fish tail to propel themselves. On land, they move by flopping along on their bellies, a caterpillar-like motion called "galumphing." While this sounds slow and awkward, seals can move quite quickly when they wish to!

On the other hand, sea lions and fur seals have large front flippers that carry a lot of strength. In the ocean, these animals swim by using their front flippers like powerful oars. Sea lions and fur seals can also move more quickly on land than true seals, and can even climb well, as they can bring all four flippers underneath their bodies and walk on them.

Can you spot some of these differences in our pinniped patients below?

How They Sound and Behave

If you’ve ever spent the day relaxing on a California beach or walking around PIER 39 in San Francisco, you’ve likely heard the noisy barking of California sea lions. As a very social species, sea lions vocalize these boisterous barks to communicate with one another. They often rest closely packed together at favorite haul-out sites on land or float together on the ocean's surface in groups called "rafts."

While vocalizations and behaviors vary from species to species, true seals are typically quieter than sea lions and communicate more through grunts, growls and hisses than the loud barking of sea lions. Exceptions to this include northern elephant seals, a species that can produce extremely loud and trumpeting calls. Many seal species are also less social than sea lions, often leading solitary lives with more time spent in the open ocean outside of breeding season. Curious about these marine mammal noises? Click to hear a diverse symphony of sea lion and seal vocalizations.

Although part of the otariid family along with sea lions, species such as northern fur seals and Guadalupe fur seals spend the vast majority of their lives at sea and are thought to be mostly solitary while at sea. In fact, after northern fur seal pups separate from their mothers at 4 months old, they embark into the open ocean and generally don’t return to land for two years!

California sea lion

Northern elephant seal mom and pup

Hawaiian monk seal

Rehabilitating Sea Lions and Seals & Prevalence of Diseases

Sea lions and seals can be found all over the world, with different species adapted to live in different climates and habitats. Along 600 miles of California coastline, the Center rescues and cares for animals in the otariid family such as California sea lions, Steller sea lions, northern fur seals and threatened Guadalupe fur seals. Within the phocid family, we rescue true seals including Pacific harbor seals and northern elephant seals.

On Hawai‘i Island and Maui, we are also the lead responder for endangered Hawaiian monk seals. In fact, we operate the only hospital dedicated to this species, Ke Kai Ola. The Hawaiian monk seal is one of the most endangered seal species in the world, and conservation efforts are critical to their survival.

Similar to a human hospital, our expert animal care staff and volunteers provide the highest quality health care for our marine mammal patients. Every animal that comes through our hospital doors receives an individualized treatment plan based on their medical and health needs, and in consideration of their species, age and body condition.

Animals are admitted to our hospital with a range of ailments, and a difference between seals and sea lions is the prevalence of certain diseases. For example, the majority of our patients suffering from leptospirosis, domoic acid toxicosis and cancer are California sea lions.

In fact, our veterinarians may suspect leptospirosis in a sea lion even before laboratory tests confirm this diagnosis due to some distinctive behavioral symptoms, which include the animal drinking water and folding its flippers over its abdomen. Patients diagnosed with leptospirosis are treated with antibiotics, fluids and other supportive care.

Many of the physical and behavioral differences between seals and sea lions inform not only how we rehabilitate our patients, but also the research we conduct into marine mammal health and emerging diseases.

Our research has also shown that nearly 25 percent of adult California sea lions are developing cancer. In order to study this cancer, we collect samples from each patient, fostering greater understanding of what might be causing the alarming cancer occurrence in sea lions—including environmental and genetic factors.

While there is more to be learned about the complex factors that play into the development of this disease, what we learn from these sea lions contributes to research that could eventually lead to cures for humans.

Each animal has a story to tell, and we are able to take what we learn from the hundreds of seals and sea lions we rescue each year to gain valuable insight into ocean health. Together, this information helps us better understand how to protect these animals and our shared ocean.

Caring for Newborn Pups

Wildlife harassment by people and off-leash dogs is unfortunately one of the most common reasons young seals and sea lions are rescued, and they arrive at our hospital with distinct medical needs.

Around springtime, harbor seal mothers temporarily leave their newborn pups on the beach as they go out to sea to search for food. This species is also easily stressed by human presence. Sadly, harbor seal pups are often separated from their mother much too soon due to people or dogs getting too close, which can scare the mother away and cause her to abandon her dependent pup.

Many orphaned harbor seal pups are rescued at just a few days old with under-developed immune systems, leaving them in a very fragile health state. In order to limit their exposure to the diseases many of our older seal and sea lion patients carry, these pups are housed in their very own harbor seal hospital, designed especially to meet their needs during this highly vulnerable age.

Since very young seal pups would still be nursing with their mother in the wild, our animal care experts feed them a special formula through a tube to make sure they get vital neonatal nutrients in their diet, then introduce them to a fish diet once their teeth have come in.

For other orphaned pups like Steller sea lions, a very social species that has an especially high risk of habituating to humans, additional precautions may be taken to further avoid human contact. For example, to reduce the need to handle a newborn Steller sea lion pup named Colby, our veterinary experts diligently coaxed him to transition from tube feeding to bottle feeding within days of his arrival.

Colby’s bottle was then attached to the hospital pen wall so he could drink the nutritious formula without being held—greatly reducing the chance of this sea lion associating food with people at such an early age. He was also housed with California sea lions to develop critical social skills necessary in the life of an otariid.

Seal vs. Sea Lion Enrichment

To ensure our patients are physically and mentally prepared to thrive in the wild, the Center incorporates animal enrichment into our care protocols. Our experts design innovative enrichment for specific species, as well as items that are safe for both seals and sea lions. As an educational tool during rehabilitation, enrichment encourages species-typical behaviors while helping our patients develop crucial problem-solving and survival skills.

As we observe the intricacies of seal and sea lion behaviors, differences in foraging strategies come to light when these animals engage with certain items. For example, when introduced to the “honeycomb” enrichment, a sturdy box covered in holes and stuffed with fish, our patients use a number of unique tactics to get the fish out.

Pacific harbor seals and northern elephant seals show similar strategies like sticking their noses in the holes, pushing the honeycomb around, swimming on top of it, and flipping it over and around. Harbor seals also use their front flippers to claw and scratch the holes while elephant seals are a little less active.

But when California sea lions and Steller sea lions interact with the honeycomb, everything moves fast. The sea lions swirl around the honeycomb, seemingly assessing the fish inside and calculating their strategy for getting them out.

While sea lions also use tactics like poking in their noses and flipping or pushing the honeycomb around the pool, their agility and strength allow them to utilize additional strategies like pushing the box to the bottom of the pool so they can move the fish toward the holes and pull the fish out.

The differences in how seals and sea lions interact with enrichment are likely due to how these species hunt for food in the wild. For example, while elephant seals feed on bottom-dwelling creatures and may not need to know how to finagle fish out of a rock crevice, sea lions utilize a wider variety of tactics to find and catch food.

As our experts continue building new pinniped enrichment, designs for sea lions may need to be more complex because they have more foraging strategies in their mental toolbox that should be practiced.

You Can Make a Difference

Now that you know how to recognize seals and sea lions, learn how you can help protect them. Impacts from human activity—such as climate change, plastic pollution and unsustainable fishing—threaten marine ecosystems vital to marine mammal health and our own health. The greatest threats to seals and sea lions are caused by people, but we can also be their greatest champions.

You see, it’s people like you who make it possible for sick and injured animals to get the critical care they need to be successfully returned to their ocean home. Your contribution goes a long way to help individual patients as well as support scientific research that will help ensure a healthy ocean future for marine mammals and humans alike.

Yes, I want to save a life!

Yes, I want to save a life!

You’ll be giving sick and injured animals the best possible care at the Center’s state-of-the-art hospital. With your gift today, you are giving a patient a second chance at life in the wild.

See Our Latest News

{"image":"\/Animals\/Wild\/Elephant seal\/cropped-images\/wild-es-ano-nuevo-photo-by-clive-beavis-159-0-1270-992-1772151576.jpg","alt":"wild northern elephant seal at ano nuevo state park","title":"Avian Influenza Confirmed in Northern Elephant Seals","link_url":"https:\/\/www.marinemammalcenter.org\/news\/avian-influenza-confirmed-in-northern-elephant-seals","label":"News Update","date":"2026-02-26 01:00:00"}

{"image":"\/Animals\/Wild\/Gray whale\/cropped-images\/two-gray-whales-golden-gate-bridge-shutterstock-0-0-1270-992-1770234810.jpg","alt":"two gray whales under the Golden Gate Bridge","title":"The Marine Mammal Center and San Francisco Harbor Safety Committee Pilot New Vessel Operator Training Program","link_url":"https:\/\/www.marinemammalcenter.org\/news\/the-marine-mammal-center-and-san-francisco-harbor-safety-committee-pilot-new-vessel-operator-training-program","label":"Press Release","date":"2026-02-06 01:00:00"}

The Marine Mammal Center and San Francisco Harbor Safety Committee Pilot New Vessel Operator Training Program

February 6, 2026

Read More{"image":"\/Animals\/Wild\/Bottlenose dolphin\/cropped-images\/dolphinphoto-by-adam-li-c-noaa-0-0-1270-992-1769539954.jpg","alt":"A bottlenose dolphin jumps out of the water.","title":"What\u2019s the Difference Between Dolphins and Porpoises? And Other Animal Trivia","link_url":"https:\/\/www.marinemammalcenter.org\/news\/whats-the-difference-between-dolphins-and-porpoises-and-other-animal-trivia","label":"News Update","date":"2026-01-26 23:00:00"}

What’s the Difference Between Dolphins and Porpoises? And Other Animal Trivia

January 26, 2026

Read More{"image":"\/Animals\/Patients\/Sea otters\/2025\/cropped-images\/so-mooring-release-2-laurie-miller-c-the-marine-mammal-center-USFWS-permit-MA101713-1-147-8-1270-992-1770307740.jpg","alt":"Sea otter - Mooring","title":"Rescue Stories: Southern Sea Otter Mooring Named the 2025 Patient of the Year","link_url":"https:\/\/www.marinemammalcenter.org\/news\/rescue-stories-vote-for-your-favorite-marine-mammal-patient-of-2025","label":"News Update","date":"2026-01-16 10:05:08"}

Rescue Stories: Southern Sea Otter Mooring Named the 2025 Patient of the Year

January 16, 2026

Read More