Adaptations of the Deep: Seal Whiskers and Eyes

- Behavior

- Natural history

- Medicine

Sensitive whiskers and big eyes are amazing adaptations that help seals and sea lions survive in the wild. Learn how these animals put these adaptations to use to forage for food in the murky ocean and how experts at The Marine Mammal Center care for our patients with eye conditions.

How a seal’s whiskers and eyes help it forage

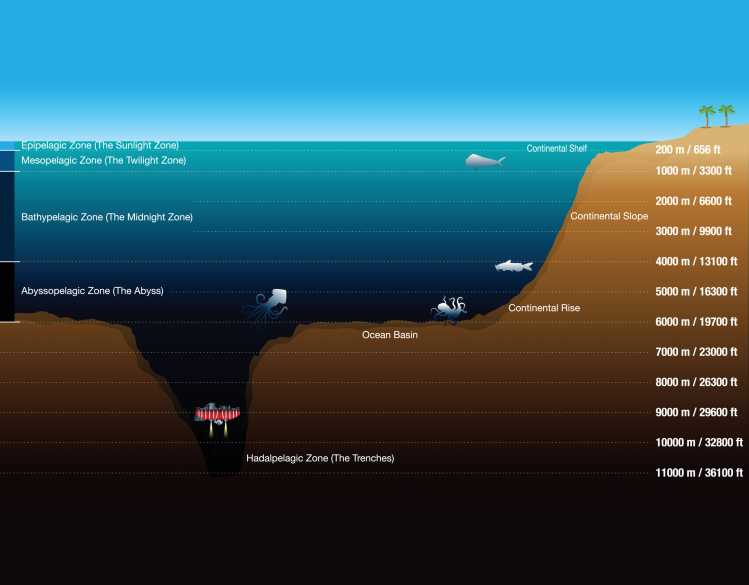

In the ocean, sunlight decreases rapidly the deeper you are. Only a small amount of light can reach below about 650 feet in the deep-sea area known as the mesopelagic, or twilight zone. And beyond about 3,300 feet, the bathypelagic, or midnight zone, is bathed in complete darkness.

Many seal and sea lion species can dive to the twilight zone, and some can even descend into the midnight zone. Northern elephant seals, for example, are among the deepest diving mammals, capable of swimming to depths of more than 5,000 feet as they migrate, avoid predators and forage for food. But in the dark waters of the deep ocean, how do marine mammals even find their prey?

Seals and sea lions are highly adapted to life underwater as well as on land. With big eyes that include rounded lenses and large pupils that fully open underwater, they adapt very quickly to decreasing light levels as they dive deeper. A special layer in the back of their eyes, called the tapetum lucidum, also helps absorb more light to see better in the dark, murky ocean and find prey.

Additionally, their extremely sensitive vibrissae, or whiskers, can detect vibrations in the water to sense their prey. Each seal whisker has about 1,500 nerve endings gathering and relaying vital sensory information about the animal’s environment. With so many nerve endings, seal whiskers are the most sensitive in the animal kingdom (for comparison, cat whiskers only have about 200 nerve endings each).

This adaptation helps seals and sea lions hunt because their prey create a wake, or movement, in the water as they swim. Sensitive whiskers can pick up on this movement, helping the marine mammal to focus on and follow the fish, squid or other prey. These unique animals can also control their whiskers, protracting and retracting them in a rhythmic motion, to help them search for food.

As elephant seals swim in the pitch-black waters of the midnight zone, their whiskers allow them to track and catch prey even when they cannot see. In fact, largely thanks to their incredible whiskers, some seals with impaired vision or blindness have also been known to thrive in the wild.

Treating patients with eye conditions

Reduced vision or total blindness in seals and sea lions is not as uncommon as you might think. Having large eyes is a great adaptation for seeing in dark water, but the cornea (the clear outer covering of the eye) can be easily injured. Once the cornea is damaged, it is easier for a serious infection to occur.

There are many causes of impaired vision in patients we care for at The Marine Mammal Center. And thanks to supporters like you, our veterinary experts have the tools needed to treat marine mammals with trauma or infection of the cornea, as well as eye diseases like cataracts and glaucoma.

How we treat eyes and restore vision depends on the type and depth of damage, and common treatments can include eye drops, antibiotic gel and surgery. If an animal’s eye is so injured or infected that treatment has not worked, we may also perform an enucleation, a surgical procedure in which the damaged eye is removed.

Enucleation was the best option for Coyote, an elephant seal pup that was admitted to our hospital malnourished and with a severe injury to his right eye. The surgery was a success, and after four months of life-saving care, he was given a clean bill of health. Thanks to caring people like you, Coyote was released back to the wild with one eye and a second chance.

Explore the photo slideshow below to see more of Coyote’s journey from rescue to release.

At our hospital, all marine mammal patients receive bright orange flipper tags with identification numbers. This allows us to track individuals if they are spotted again in the wild throughout their lives. When we resight patients, like elephant seal Sentinel, our experts can gain important insights that help improve the care we provide and our long-term impact on advancing ocean health.

Sentinel was rescued as an adult with parallel bleeding wounds that were likely caused by a boat propeller. After she was brought to our hospital, our animal care experts cleaned and treated her wounds to support her recovery.

By observing Sentinel’s movements and behaviors in her pen, such as using her whiskers to guide her, animal care experts also suspected that this seal was blind or had extremely low vision in both eyes. Sentinel received a thorough eye exam as part of her admit evaluation, including an ocular ultrasound, an imaging technique that uses high-frequency sound waves traveling through the eye.

Our veterinarians determined that the blindness was likely a long-term, chronic condition with which she had learned to survive well before her propeller injuries had occurred. In fact, as experts examined Sentinel’s body condition and overall health, they saw signs revealing that she was eating enough food and had potentially even given birth to a pup in recent months.

Each patient’s rehabilitation is approached with a holistic view, taking into account the animal’s clinical health and wellbeing, natural behaviors, and ecology. Given that Sentinel’s wounds had begun to heal, she was previously catching prey with low to no vision, and she was in otherwise good body condition, after just a few days in care our experts determined that the best place for this seal was back in her ocean home.

More than a year after Sentinel’s release, she was spotted on a California beach looking very healthy, and her wounds had healed fully and well—positive signs that she had been using her natural instincts and sensitive whiskers to continue to forage effectively.

Learning from patients to create a healthier ocean

As we diagnose, care for and track our patients, we’re not just learning about the specific diseases and injuries that affect marine mammals, we’re also learning about the health of the ocean as a whole. Marine mammals serve as sentinels of the sea, alerting us to the dangers they face that can also affect us.

As the world’s largest marine mammal hospital, the Center is able to collect and process thousands of samples from our patients as part of our ongoing disease investigation research. Results from these samples support our scientists in identifying diseases and pathogens in our patients, investigating the reasons why marine mammals strand, and determining how these factors are connected to ecosystem and human health.

In addition to being a critical adaptation that helps marine mammals to forage, the chemical composition of sea lion and seal whiskers can also reveal a lot to scientists about the animals’ diets in the wild. The Center’s scientists collect a whisker sample from each of our Guadalupe fur seal patients prior to their release, and provide these unique research samples to our partners at NOAA for nutritional analysis for critical monitoring of this threatened species following a recent Unusual Mortality Event (UME).

What we learn from our patients can help reveal alarming ocean health threats, and this knowledge helps us decide what actions to take to better protect these animals as well as future generations. Did you know it’s only because of people like you that this life-saving care and research is possible? Your support helps return marine mammals like Coyote and Sentinel to a healthier ocean home, where they can interact with other wildlife, embark on incredible migrations, and continue diving to the darkest depths foraging for food.

Our patients rely on the generosity of people like you. Help save lives all year long by becoming a monthly supporter.

Yes, I want to save a life!

Yes, I want to save a life!

You’ll be giving sick and injured animals the best possible care at the Center’s state-of-the-art hospital. With your gift today, you are giving a patient a second chance at life in the wild.

See Our Latest News

{"image":"\/Animals\/Wild\/Gray whale\/cropped-images\/two-gray-whales-golden-gate-bridge-shutterstock-0-0-1270-992-1770234810.jpg","alt":"two gray whales under the Golden Gate Bridge","title":"The Marine Mammal Center and San Francisco Harbor Safety Committee Pilot New Vessel Operator Training Program","link_url":"https:\/\/www.marinemammalcenter.org\/news\/the-marine-mammal-center-and-san-francisco-harbor-safety-committee-pilot-new-vessel-operator-training-program","label":"Press Release","date":"2026-02-06 01:00:00"}

The Marine Mammal Center and San Francisco Harbor Safety Committee Pilot New Vessel Operator Training Program

February 6, 2026

Read More{"image":"\/Animals\/Wild\/Bottlenose dolphin\/cropped-images\/dolphinphoto-by-adam-li-c-noaa-0-0-1270-992-1769539954.jpg","alt":"A bottlenose dolphin jumps out of the water.","title":"What\u2019s the Difference Between Dolphins and Porpoises? And Other Animal Trivia","link_url":"https:\/\/www.marinemammalcenter.org\/news\/whats-the-difference-between-dolphins-and-porpoises-and-other-animal-trivia","label":"News Update","date":"2026-01-26 23:00:00"}

What’s the Difference Between Dolphins and Porpoises? And Other Animal Trivia

January 26, 2026

Read More{"image":"\/Animals\/Patients\/Sea otters\/2025\/cropped-images\/so-mooring-release-2-laurie-miller-c-the-marine-mammal-center-USFWS-permit-MA101713-1-147-8-1270-992-1770307740.jpg","alt":"Sea otter - Mooring","title":"Rescue Stories: Southern Sea Otter Mooring Named the 2025 Patient of the Year","link_url":"https:\/\/www.marinemammalcenter.org\/news\/rescue-stories-vote-for-your-favorite-marine-mammal-patient-of-2025","label":"News Update","date":"2026-01-16 10:05:08"}

Rescue Stories: Southern Sea Otter Mooring Named the 2025 Patient of the Year

January 16, 2026

Read More{"image":"\/People\/Action\/Veterinary care\/cropped-images\/Harris_Green turtle_TMMC-0-0-1270-992-1767649941.jpg","alt":"Heather Harris","title":"Seattle Aquarium Awards Dr. Heather Harris With Prestigious Conservation Research Award","link_url":"https:\/\/www.marinemammalcenter.org\/news\/seattle-aquarium-awards-dr-heather-harris-with-prestigious-conservation-research-award","label":"In the News","date":"2026-01-05 04:48:00"}

Seattle Aquarium Awards Dr. Heather Harris With Prestigious Conservation Research Award

January 5, 2026

Read More